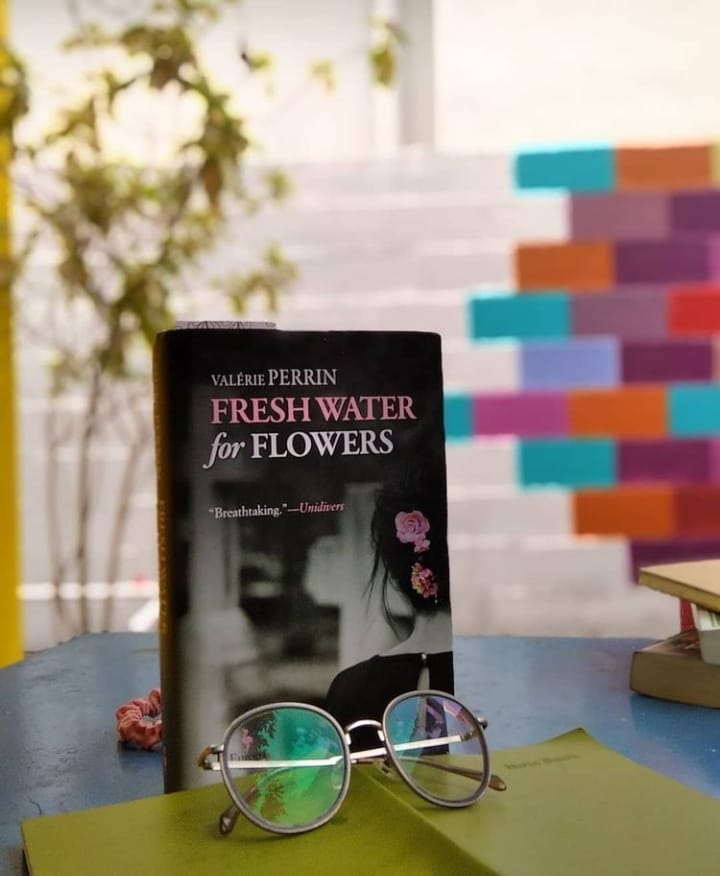

Fresh Water for Flowers

//The lockdown in India simmers and coils and flattens itself on my verandah – every afternoon, bristling with its scales of heat and the rain clouds teasing and retreating, full of sharp malice. I haven’t sat in a cafe and looked out of the window into nothingness, whilst the waitress with her neat apron serves me a good cappuccino. It has been farther than I can remember. Sometimes that’s the thing I miss the most – sinking into an arm chair at a bistro – any damn bistro – with a good, cozy book.

The new Spanish word for the week had been – Aventura. Meaning – Adventure. And it was going to be while before I had any sorts of aventura in my life – with a Spanish one seeming even more distant.

Vicarious is what I threw around my friends in France and London when they stepped out for coffee, with their furtively shrinking lockdowns and their part of the world finally relenting them, a tiny morsel of open-skied happiness and coffee in Styrofoam cups.

I told them, “I am drinking that coffee through you, vicariously.”

Emma disrupted my afternoon siesta with a strident voice note, “Bunny! I am going to gift myself an ‘aventura’. I know this is crazy, but I am going to drive for 90 Kms and go see my favourite author and give her my illustrations and get my book signed. It’s even more crazy when I tell you this – but I am going to pull myself out of this glum, and do this. Okay? Ciao!”

I reply back, in my croaky-doom-is-upon-us-afternoon voice, deplete of all cheer.

“No.

Not Crazy.

You deserve this aventura.

I am going to go on this aventura with you, Vicariously.

Meeting an author is never a bad idea, even if you have to cross the narrow seas of the Dothraki.”

I feel happy about the Game of Thrones reference – and I remind myself to rewatch season 6.

Emma comes back from her adventure and she doesn’t update me, and I also forget to ask.

I don’t even ask her the name of the author – which is very unusual for both of us because we’ve had a million conversations about how we were going to uncover the regular café that Margaret Atwood goes to, in Toronto and ambush her, on an unsuspecting afternoon.

I later think to myself about who this usurper is, that has ousted Atwood from her throne, but I don’t follow through.

And then I stumble upon the most beautiful first page, existing in flesh and blood, in the present, in this mortal world, in all this unspeakable bleak, in all of this colourless, odourless world – shimmering like a new sequinned dress on display at store unveiling its spring collection.

//

1.

when we miss one person,

Everywhere becomes deserted.

My closest neighbours don’t quake in their boots. They have no worries, don’t fall in love, don’t bite their nails, don’t believe in chance, make no promises, or noise, don’t have social security, don’t cry, don’t search for their keys, their glasses, the remote control, their children, happiness.

They don’t read, don’t pay their taxes, don’t go on diets, don’t have preferences, don’t change their minds, don’t make their beds, don’t smoke, don’t write lists, don’t count to ten before speaking. They have no one to stand in front of them.

…….

They’re dead.

The only difference between them is in the wood of their coffins: oak, pine, or mahogany.//

I run my fingers over it, touch the words, draw circles around them and I start to dissolve.

The coming weeks, I dissolve further – obliterating all human contact, cursing each impatient caller, annoyed at having to bathe, eat and sleep as rigours of daily upkeep, cancel on zoom calls, feign illness, and slide deeper under my blanket.

I’ve moved to Burgundy and I’ve inhabited the world of Violette Toussiant, keeper at Brancion-en-Chalon cemetery. There’s Nono, Gaston and Elvis – the gravediggers, about twelve cats, plaques, funerals, poetry, fresh mud, strong mulsh, ripe tomatoes, plenty of tea, and a kitchen whose aroma I can sniff off the pages, for its candour and warmth.

What better place to speak of the truth and its insides, other than a grave?

What better place to encounter humans in their unfine, unsurrendered, un-airbrushed, vulnerable beautiful selves, other than a grave.

The grave is the receptacle of the unrequited – one pours into it, things and objects and whispers that they want carried into another world, a world always known for its abrupt, dramatic entrances. And in the misgivings, failings, weekly visitations and unrequited confessions, of all these humans of Burgundy – that Violette diligently records, in her notebook, and her garden of chrysanthemums, and reads to us – we, the unsuspecting readers, find it in ourselves to find the tiny morsel of bravery to get through another week, another day, another ounce – of this unrelenting life.

“I feel like being alone. Like every evening. Speak to no one. Read, listen to the radio, have a bath. Close the shutters. Wrap myself in a pink kimono. Just feel good.

Once the gates have been shut, time belongs to me. I’m its sole owner. It’s a luxury to the owner of one’s time. I think it’s one of the greatest luxuries human beings can afford themselves.”- page 49, chapter 11.

Violette reminds you, of you.

Violette is what you do and who you are, when you turn the lights out, indulge yourself with some wine or green tea, hang the “we’re closed” sign on your shop door, and allow yourself to pucker your face and wrinkle your nose, at your unshaven legs and all the disarray around you. Violette is all of us, on our bad days.

And Violette is indeed all of us, on the days where we bestow kindness, push the last piece of cake across the table, choose the seat with the draft, send your friend a book, and relinquish the prettiest bunch of carnations to another woman that needed it way more than you.

“On a daily basis, there were two things to pay attention to: not locking visitors in – after a recent death, some mourners lost all notion of time – and watching out for theft – it wasn’t uncommon for occasional visitors, to help themselves, from neighbouring tombs, to fresh flowers and funerary plaques. (“To my grandmother,” “To my uncle,” or “To my friend” could apply in most families.)

And Violette’s kitchen door was always open – there was a simmering pot of chamomile tea, sometimes she left it out for whoever walked in even when she was in the backyard tending to her beans and eggplants, she made sandwiches for the gravediggers, they convened in her tiny kitchen every morning and went over the day’s schedule, even on days that nobody died they had things to do, they spoke of the town, they spoke of the dead, they spoke of the living and the prowling cats that were always hungry. Violette let the mourners in, some of them came back years later and asked for the location of a buried mother or a grandmother – she gave them the location, without blinking, without rummaging through registers and drawers; some came back and muttered wistful eulogies to her in the kitchen, not having made it to the funeral – she fished out a register and read the proceedings of the funeral, even from ten years back, complete with anecdotal details – “it was raining hard and there were thirty three people”- she was precise to the point of thirty three – not a plus one or a minus one.

On the second week with this book, I had posted a quote from this book on Facebook.

“When someone falls in love with you, the weather is marvellous.”

– With a sunny picture of the garden in my backyard, that was piece of Morocco, Burano and Pondicherry, all sliced up together harmoniously.

Emma responded to this with, “Bunny! Are you reading Fresh water for Flowers? This is who I went to see – 90 kms away!”

The usurper had been Valerie Perrin?

“You met THE Valerie Perrin?”

“I did.”

“The book is a raft. Isn’t it?”, Emma asks me. “It saved me during the first wave, and looks like it’s saving you – in this second wave.”

“Oh God, yes! This book is a raft.”

This book was a raft – it had found us, in our desolate islands of solipsism, where we kept our heads down and mired our spirits in drought, and on most days – forgot to disentangle the low hanging boughs and let the sunshine in.

In Violette’s cemetery we had found some room.

Love is used – often very blithely, with scant respect, for its power or perimeter. Love isn’t available everywhere or in places that we go looking, and most times – we may not even need it.

But what we all do need is a little room, for ourselves.

From time to time.

Where we could pucker our faces and droop our shoulders and keep our heads down, and not entirely drown.

This book was a raft.

It gave us both, plenty of room.//

Fresh Water for Flowers

By Valérie Perrin