Handmaid’s Tale and Testaments – and the women that came after…

The Booker 2020 is almost here and this was my review of last year’s co-winner, Testaments (that I absolutely loved) – this will be one of the most important movements about Reproductive Freedom.

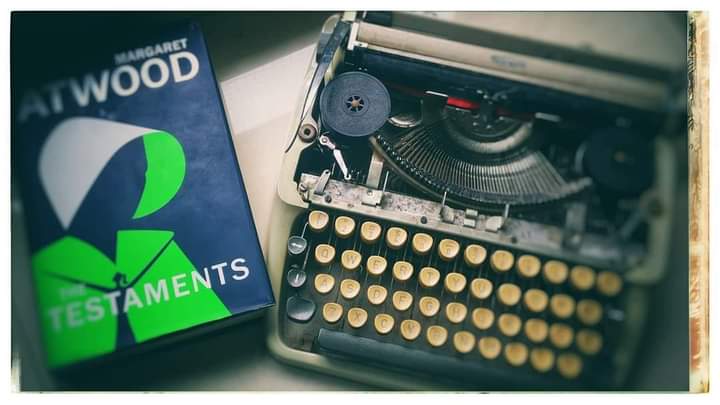

Atwood wrote The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985, the Berlin Wall still encircling her, a personal computer a coveted luxury; the novel had come to life in orphaned napkins at restaurants, scribbled notes sitting in parks, dutifully transferred to the Typists for remembrance and record. When it was out in the U.K. – it had been called a ‘trippy ride’, mostly dismissed and sporadically venerated, but largely denied any applause. The Handmaid’s Tale saw a bewildering resurgence in the Trump Era, frontiering the festering misogyny and the derailed reproductive freedom that came as decree. Offred became June, and Elizabeth Moss took home an Emmy. And the world stood in thrall, stunned and quietened.

Testaments arrive, amidst the soaring fervor the Handmaid’s Tale sits in, patiently waiting for the back story or the sequel or the feared End to a Moira or an Offred. The last page of The Handmaid’s Tale circled over Offred being grabbed and whisked away into a black, terrifyingly smothering van. We didn’t know for sure if she was pregnant and we didn’t know for sure if she lived.

Aunt Lydia, the Iron Clad perpetrator of the regime, the emblem of the tenacity of Gilead, the Tallest embodiment of Puritan virtue, a character that you detested deeply and with all of your might, turns storyteller in Testaments – she breaks the fourth wall, gazes at you – the reader, and whispers ‘perhaps, reader, you will never materialize, you’re only a wish, a possibility, a phantom’.

And right there, is Atwood’s brilliance in ploy and weave. The archvillain tiptoes around Gilead and she draws you in, whether you like it or not. Atwood lives in the sentences she writes, the nuance of her imagined construct, each a follicle that descends into your skin; if sentences were to suddenly become a religion, Atwood would be the Knight’s Templar!

“We were snares and enticements despite ourselves, making them drunk with lust, so they’d stagger and lurch and topple over the verge” – this is what Gilead’s little girls are raised to subscribe to – enticing a man, was causing him peril, causing his moral devices to flounder and fall, and any man that was subject to your snare, even inadvertently, was thereby rendered dysfunctional, in the discharge of duties that were sacrosanct and cardinal. The little girls were only taught to embroider – your life’s repertoire depended on whether you could successfully pull off a chain stitch, with supreme delicacy.

And of course, books were banned. The only allowed reading was the Bible that had to be remembered by rote, fervently quoted and often; and the Bible was ‘read to you’. The girls of Gilead were not taught to read. You were allowed to read only if you became an Aunt because Aunts did not procreate and thus could be dealt with a skill. They could hence teach girls and prepare them for marriage and inculcate all habits, quintessential for the good wife. The girls were deemed ready to marry at thirteen and a Lord Commander, preferably the oldest of them, gleaming with stars and shining lapels, made for the perfect groom. Most of them had thinning hair, yellowed teeth, and gruesome pallor – but women had no claim to ornament or aesthetic, they were only required to serve and bear children.

“Once I had enough hair for a top knot, in the days of top knots, for a bun, in the age of buns. But now, my hair is like our meals, sparse and short”- writes Aunt Lydia. The first thing that they did to the women was to freeze their bank accounts and obliterate beauty or any form of decoration. The women resembled each other, in their misery, awash in the sparseness of colors, dressed in bleak to cover and conceal. How Gilead became Gilead and how Aunt Lydia became Aunt Lydia, are told in scalding overtones, the engulfing world revealed slowly and languorously, the construct of the scenes morbidly playing out in your head in blood-curdled red and grey. There is no escaping Atwood!

In constructing Gilead, the women are herded to a stadium and not allowed to relieve themselves. They slowly rot into the unkempt, bathed in their own putrid smells and their souls reduced to a limp withering. As the days blur, and their captivity festers, the women ossify into creatures of neglect and dilapidation, their collective wills quivering and worn out. And in this decrepit morass, we see the birth of Aunt Lydia, a Chief Justice in pre-Gilead, who is baited with a clean bathroom in a hotel room, with clean sheets and running water and food that isn’t an onion soup. “The Bathroom was white, I had forgotten how white looked like”- she writes.

The plot itself is racy, and every page is furiously turned, in a never-ending conflict between dwelling on the beautifully crafted sentences to unearthing the turn in the weave. Testaments is narrated through the POV of Offred’s daughters, hence we never get to see Offred, but she’s a phantom, an ethereal dwelling, a footprint, a rustle, a grip, in the pauses.

Testaments end with hope; does not leave the reader stranded in the oppressive wilderness of Puritanism, speaks to you about the inevitability of the Resistance, and the triumphant grit in the pip-squeak of numbers that choose to stand against, that know they are affronting a Goliath, but don’t balk anyway.

Aunt Lydia, in her final sermon to us readers, writes- “I hope the Lipstick has made a comeback in your times. They didn’t exist during ours”

After clamping the last page shut, of my beautiful hardcover, I smeared some startling red lipstick and went out, met the girls, and bought each of them a dark, purple-pink concoction of lip paint, titled ‘The Witch’s Snare’.

This wasn’t a book, this was a phantom walk into the throes of Gilead, right into the seams of its tyranny.

Leave a Reply