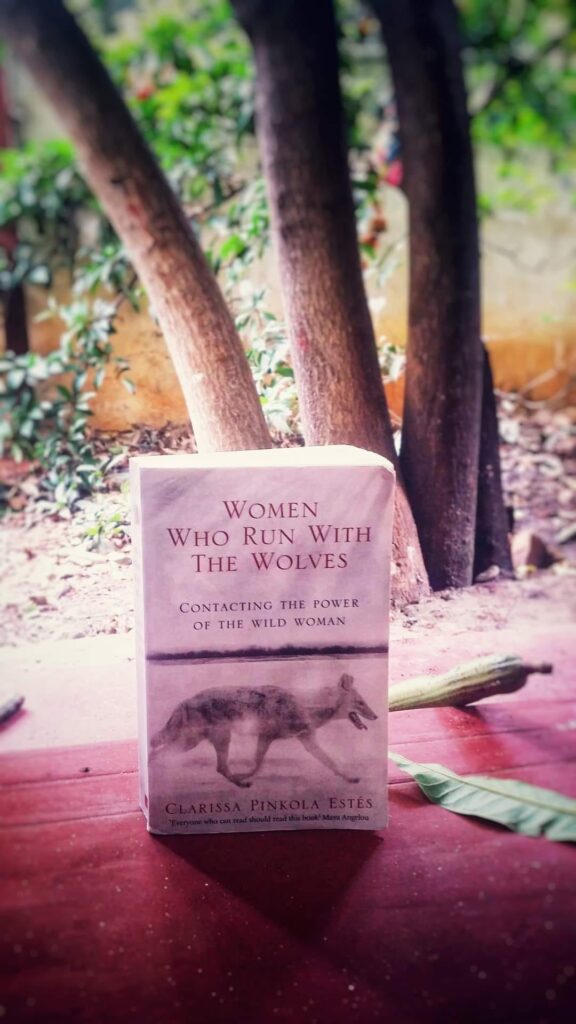

Women who run with the Wolves

‘Everyone who can read should read this book’- says Maya Angelou, on the ebbing, porously pale cover of this book.

The modest cover also has a rendition of a wolf – ‘La Loba’.

It’s thick, it’s a 500 pages and sits unpretty, unornamented, amidst fellow book spines, teetering piles of colour and froth, of vivid brushstrokes and rampant illustrations and gleaming brown leather of the hardbounds – but I pick her up, and look around, “Is there an older copy? Is there a discount?”- the Proprieter at Blossom, Bangalore, nods to me, he puts his billing on halt, and agrees to go look for an older copy.

I am an important customer you see – I am known to have displayed immense staying power and sitting proclivities on his mosaic floors, he has seen me on seven evenings in a row, demanding titles from every country, turning over covers and examining for vandalistic underlinings and markings, and going back with a sack, and a truckload of bookmarks. He’s miffed about the bookmarks, I can see.

He smiles when I ask him, “Do you have any more Atwood bookmarks?”, but I can see that he doesn’t want to indulge me. Though he stays willing and encouraging for most part, he agrees to ferret out an older copy, that has a formidable hole punched into the back of the spine, that runs deep into a few pages bottom up.

I say, “I’ll take it.”

Aren’t we all made and unmade by punctured holes and fractured spine?

And this dent, this wound on the book, saves me 80 bucks – I get the book for 400 bucks.

I decide to read it on my birthday month.

“Take your time reading. The work was written slowly over a long period of time. I wrote, went away, thought some more, and came back and wrote some more. Most people read this work the way it was written. A little at a time, then go away, think about it, then come back again.”- writes the Author, Clarissa Pinkola Estès to us, in a ‘note to the reader’.

Only this afternoon, a lovely, exquisite woman I know wrote to me asking -“but why did this happen to me? I’ve never done wrong, I’ve never been mean or spiteful, and yet I am having to go through this – I don’t deserve these people”.

Nobody does – nobody really deserves their life to be populated, by dint of compelling traditions or cultural overlays,

people and circumstances – that render our work half done and unburnished,

that leave our soul diminished and quenching, that leave our palms blistered and lacerated and coarsened,

that infantalize our words and rage,

that sever passion but deepen prejudice, that eventually push us to an irreducible minimum.

And yet, as women – we constantly see this. We show them our art, and they look with disdain at the silvery cobwebs swirling around our grotty stairwells and piling dust on our bookshelves,

we show them our resolute muscle and the will to not cower down in battle – they tell us we need to knead the dough and bake our breads and invest our bristling fires in good house keeping.

Our work is constantly assessed and backed up against how we fare as people – are we polite?

Are we smiling?

And smiling some more?

Do our kids look fed and clothed and manicured?

Are we too loud?

Too sexy and too brimming?

And every womxn finds herself standing on a threshold – a threshold of its own colours, its own smells and cadence, its own lighting and curtains, pushing her farther away from the known and the familiar – toward an unknowable and unholdable, with the strange scent of the woods, the hinterlands and minty clay of the resolute sapling.

“if you don’t go out in the woods, nothing will ever happen and your life will never begin”

If you listen closely, the wolf in its howling is always asking the most important question,

Not where is the next food,

Not where is the next fight,

Not where is the next dance?

But the most important question,

In order to see into and behind,

To weigh the value of all that lives,

Where is the soul?”

– Canto Hondo (the deep song)

Imagine metaphorically trawling the forest, everybody told you not to go into the forest,

but you did,

you did anyway,

You kept walking and there were low lying branches and encumbering twigs and your feet crunching against hardened mud,

your eyes strained for the solitary sunlight,

Gossamered by the tall trees and the thicket of leaves,

only parting to reveal a primeval darkness,

but you kept walking,

and walking,

And finally you see a hut.

(Yes a hut – when was the last time we used this primordial three letter word?)

You see a hut and there comes the wafting aroma of good soup and strong bones and you trudge ahead,

your knees scraping the stubborn remains of your will,

you fall and you crawl and you finally reach the door,

…..

What do you see?

A wizened old witch with an aquiline nose, gnarled hands and a hungry throat, stirring a cauldron…

What do you do?

Knowing you, knowing me…

Knowing the way womxn tend to be engineered

we would collapse next to the witch and declare, “you can eat me later, but could I have the soup please and can you show me where the water is so I can scrub my fingers clean?”

And of course we know how this story would proceed – the witch not only does ‘not’ eat you, but makes you a warm supper, stirs up a warm fireplace and throws a blanket around you and sits down for a chat.

She’s ‘La qué Sabe’

The One that knows.

Reading this book is like having a good, good chat with this old witch,

the one of bones and fire,

the one of gnarled hands and a life endured,

the one that listens with her fingertips –

The One that really, really knows.

La Que Sabe (she who knows, from spanish)

“We are all filled with a longing for the wild. There are a few culturally sanctioned antidotes to this yearning. We were taught to feel shame for this desire. We grew our hair long and used it to hide our feelings. But the shadow of Wild Woman still lurks behind us during our days and in our nights. No matter where we are, the shadow that trots behind us is definitely four-footed” – CPE.

And this is the centrifugal premise of this book – that within us, resides the powerful four footed wild creature that has an incredible sense of smell and the courage to keep walking, to keep trotting, of an old knowing, of instinctual self-confidence and intuitive wisdom. And we are one person – but two people. This feminine psyche that is a friend, a listener and an old witch that can keep you warm and glowing, and give you the new skin whenever you need it.

I don’t know why this book isn’t massively heard of and massively discussed at book groups and coffee shops and museums and carnivals and salons- and everywhere else that a womxn and little girls go to.

It’s incredibly hard to review this book because what can I say about it, so that you will drop everything else and pick it up, right here and right now, and use it as lexicon? As bible? As historic conversation? As the breadcrumbs that lead you in the forest? – and to have this with you, every time, every single time that someone – both known and loved, unknown and unimportant – manages to crush your self worth?

This book has 16 sections – sections that needn’t be read in any particular order, because each chapter/section is a stand alone treatise, a stand alone conversation about you.

* The chapter on Ugly Duckling discusses the Ambivalent Mother and the Collapsed Mother, that fails to protect her offspring, that fails to slam well-accepted tradition on its face, that fails to teach its offspring not to feel shame.

* The chapter on Bluebeard- is a feminist reading on how you make allowances for all the nagging traits of the boyfriend or the husband. All your friends and sisters see it – but you don’t, they tell you “his beard is rather too blue, that’s something odd isn’t it?”. But you insist, “No. His beard isn’t all that blue. You’re mad”. How many of us have dated a man that our friends have never really liked? This chapter is also a beautiful dissertation on the man that pronounces a verdict, having heard no arguments –

“This castle belongs to you. You can do whatever you want. But don’t open the room at the end of the corridor. You must NEVER open That room.”

“You can do whatever you want, but who will look after the kids if you work ten hours everyday?”

“You can wear whatever you want, but I hate dresses that come up to the knees.”

* The Chapter ‘La Mariposa’ discusses the Butterfly woman, the woman that loves her body – with the belly that hangs, and the skin untaut, and the yellow between her teeth.

I don’t think this book was written for a man.

But this book was written for every womxn and definitely for you.

Because at every chapter, you’re going to be telling yourself – “F***, this is me”.

And it’s no wonder really, that it was written originally in spanish and then was translated into a 118 other languages of the world – so that womxn, all over the world, can put their feet up, and talk…and talk. .. to the old witch.

The one that knows.

Women who run with the Wolves

By Clarissa Pinkola Estès